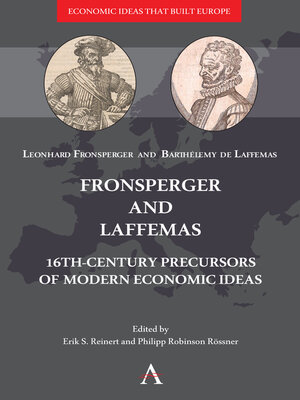

Fronsperger and Laffemas

ebook ∣ 16th-century Precursors of Modern Economic Ideas · Economic Ideas That Built Europe

By Erik S. Reinert

Sign up to save your library

With an OverDrive account, you can save your favorite libraries for at-a-glance information about availability. Find out more about OverDrive accounts.

Find this title in Libby, the library reading app by OverDrive.

Search for a digital library with this title

Title found at these libraries:

| Library Name | Distance |

|---|---|

| Loading... |

This volume introduces two unique and hitherto largely unknown contributions to the making of modern economic knowledge and makes them available internationally for the first time in full English translation. The messages of the books are seemingly contradictory, one focuses on the role of individual interests and the other on the role of government., but together they form two important pillars for the economics profession: self-interest and industrial policy.

- Written in 1597 Barthélemy de Laffemas' General regulation for the establishment of manufactures (originally in French: Reiglement général pour dresser les manufactures) is one of the earliest voices in the history of political economy emphasizing the necessity of manufacturing and large-scale industry as the source of the wealth of nations.

Located somewhat at the cross-roads between medieval Scholasticism and early mercantilism the book presents a basic version of the infant industry argument and European standard model of economic development which evolved into the works of Enlightenment thinkers such as Colbert and Friedrich List and of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century industrial policy in all the countries that followed England's path to industrialization, including the post-WW II Marshall Plan. - Leonhard Fronsperger's On the praise of self-interest (German original: Von dem Lob deß Eigen Nutzen, 1564) is the first documented instance of the 'Mandeville paradox', a theorem in modern economics usually associated with much later writings including Bernard de Mandeville's Fable of the Bees (1705/14), and Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations (1776).

|This volume introduces two unique and hitherto largely unknown contributions published in the 1500s to the making of modern economic knowledge, making them available internationally for the first time in full English translation.

- Written in 1597, Barthélemy de Laffemas' General regulation for the establishment of manufactures (written originally in French: Reiglement général pour dresser les manufactures) represents one of the earliest voices in the history of political economy – together with Italian economists Giovanni Botero (1589) and Antonio Serra (1613) – arguing that manufacturing and industry are the true sources of the wealth of nations and that states

should pursue an active industrial policy. Located at the crossroads between medieval Scholasticism and early mercantilism, it presents a political program that would lead to French economic development, providing the foundations for the French industrialization program during the 1660s-1680s. Laffemas presents a simplified version of an infant industry argument and European standard model of economic development known from thoughts of Enlightenment thinkers such as Colbert, Sir James Steuart, Friedrich List's National System of Political Economy (1841), nineteenth and twentieth-century theories for catching up with England and later the US, and the 'industrial policy' or recently 'mission-driven' policies (Mariana Mazzucato).

- Leonhard Fronsperger's On the praise of self-interest (German original: Von dem Lob deß Eigen Nutzen, 1564) is the first documented instance of the 'Mandeville paradox', one of the key axioms of neoliberalism. Commonly associated with much later writings, including Bernard de Mandeville's Fable of the Bees (1705/14), and Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations (1776), German military surgeon and polymath Fronsperger argued in 1564 that self-interest is an important driver in economic development. In his text, however, Fronsperger is much more pragmatic and less ideological than Mandeville or post-Mandevillean modern neoliberals. Vested in...