On Reading the History of Philosophy

ebook ∣ Anthem Studies in Bibliotherapy and Well-Being

By Daniel Whistler

Sign up to save your library

With an OverDrive account, you can save your favorite libraries for at-a-glance information about availability. Find out more about OverDrive accounts.

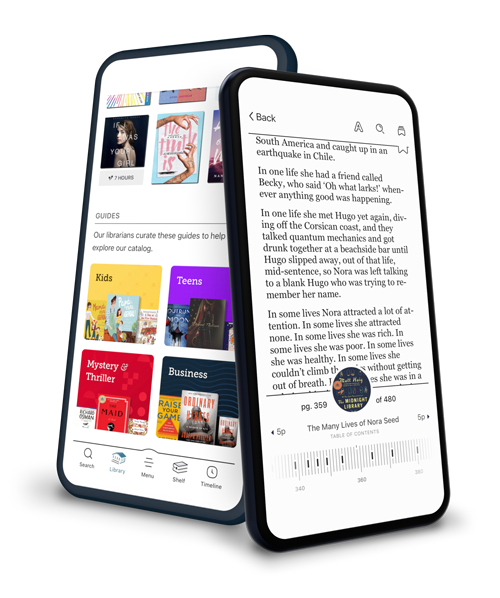

Find this title in Libby, the library reading app by OverDrive.

Search for a digital library with this title

Title found at these libraries:

| Library Name | Distance |

|---|---|

| Loading... |

This is a book about what the historian of philosophy does when reading. It is a book, therefore, that attempts to catalogue the various types of thinking produced in and through the act of reading a philosophical tex). Since Descartes, the philosopher has been persistently imagined as someone who thinks rather than reads, as someone who throws away the books handed down by tradition in order to properly begin meditating. And this binary has determined the image of the historian of philosophy too: the very practice of rational reconstruction informing so much contemporary history of philosophy is one which attempts to 'draw the curtains of words' to access what Danto called the 'pure units of philosophy' lying behind the text. Beginning from a series of problems set by Martial Gueroult, this book contests both the mutually exclusive binary of thinking and reading and the image of the historian of philosophy it gives rise to. And it does so by giving an account of history of philosophy as a readerly

|The history of philosophy is composed almost exclusively from texts. These texts look very different from each other, were produced for very different reasons and had very different functions, but, nevertheless, all of them demand an act of reading to unlock their philosophical content. And yet, the role of reading in both accessing shaping philosophical pasts has been neglected. Many philosophers since Descartes have acted as if they could bypass words when communicating ideas, and, among historians of philosophy, this tendency has been both prevalent and odd—since they spend most of their time reading.

The book seeks to redress this neglect and provide an account of—as well as a defence of—the history of philosophy as a reading practice. It brings back into focus the activity that historians of philosophy actually spend most of their time doing. However, it does not do so by way of familiar categories such as hermeneutics, rational reconstruction or analysis; instead, the book attempts to defamiliarize philosophical reading practices by asking an alternative set of questions about them: How do philosophical ideas relate to the words on the page? What is the relation between reading and thinking in philosophy? How can the reader select and arrange philosophical texts in order to create 'a history'? Who are historians of philosophy and how do certain reading practices generate and transform them?

The aim of the book, therefore, is to attend to the very thing historians of philosophy spend most of their time doing—reading.