Sign up to save your library

With an OverDrive account, you can save your favorite libraries for at-a-glance information about availability. Find out more about OverDrive accounts.

Find this title in Libby, the library reading app by OverDrive.

Search for a digital library with this title

Title found at these libraries:

| Library Name | Distance |

|---|---|

| Loading... |

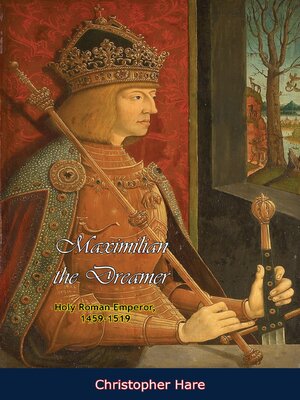

THE life of Maximilian I of Austria is not only a great historical drama of the last Holy Roman Emperor of the ancient régime, but it almost attains to the romantic interest of an epic poem, with a royal knight for its hero, in the closing day of mediæval chivalry. Maximilian stands forth as a typical figure of his time; heir to the great traditions of a Cæsar, a Theodoric, and a Charlemagne, he dreamed of mighty deeds and sought to carry out his high ideal, inspired at once by real patriotism and a lofty ambition for his race. He could never rest satisfied with the near present, but laboured with enthusiasm for distant aims whose fruition he would never see. Again and again he was doomed to disappointment in his political career, for his restless energy and many-sided point of view interfered with that narrow, dogged persistence in one definite aim which wins success. The will-o'-the-wisp of Italian conquest had an invincible attraction for him, and lured him on—as it did many a King of France—to failure and disaster. An idealist and a dreamer, the Emperor won his truest claim to greatness, not so much by his wars or his diplomacy, as by his warm sympathy with every phase of modern thought and aspiration. His keen appreciation and eager encouragement of the new spirit of the age in literature and art made him the beloved of the scholar and the poet, who both welcomed him as the ideal Emperor of Dante's vision.