Sign up to save your library

With an OverDrive account, you can save your favorite libraries for at-a-glance information about availability. Find out more about OverDrive accounts.

Find this title in Libby, the library reading app by OverDrive.

Search for a digital library with this title

Title found at these libraries:

| Library Name | Distance |

|---|---|

| Loading... |

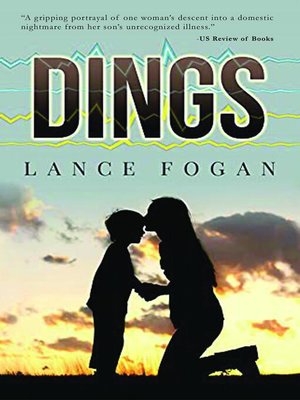

DINGS begins with eight-year-old Conner's high-fever-related convulsion. In the local ER, the doctor performs a brain CT scan and then, to rule-out meningitis, a spinal tap. The interplay of the parents and the ER staff explain the medical situation, the procedures performed, and the parents' distress. The ER doctor refers Conner to a neurologist to rule out possible epilepsy. The mother becomes distraught hearing that term; how could her bright boy have a devastating condition that could change his life, all their lives? Conner has never had a seizure and neither has anyone else in the family. "My baby cannot have epilepsy."

The novel moves then to relive earlier months with Conner failing school. His mother and school staff meet to discuss this. His father is in Iraq. Sandra resents she must deal with her son's serious school problems alone. Conner's non-convulsive epileptic mental blank-outs are not recognized by the adults. He's not fallen, he's not convulsed in an epileptic seizure. These spells are too confusing for the young boy to explain to himself or to anyone else. His schoolmates think Conner sometimes acts weird.

Psychologists and his pediatrician all miss Conner's true diagnosis prior to the convulsion on the first pages. Dad returns from his combat tour, but he is changed by PTSD. Sandra must deal with her son's school difficulties and now her troubled marriage. Then Conner's convulsion happens.

In the neurologist's office, the doctor asks if Conner ever perceives smells or tastes that aren't really there, a neurological hallmark of Conner's type of undiagnosed complex partial seizures that only a neurologist would query. These are identified by the doctor as a form of epilepsy; the youngster refers to them as his dings. The family's lives all change. The neurologist supports the parents; he explains that it's common to live a normal life if the epilepsy in the three million afflicted Americans can be controlled with anticonvulsant medications. Mother realizes her baby may never again be normal, time will tell, but they will all deal with it as do so many successful people in all walks of life.