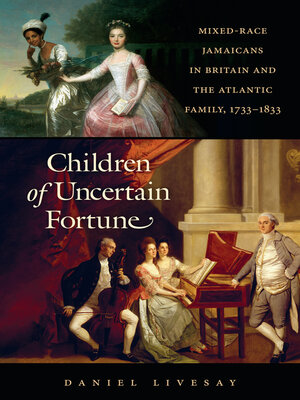

Children of Uncertain Fortune

ebook ∣ Mixed-Race Jamaicans in Britain and the Atlantic Family, 1733-1833 · Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture and the University of North Carolina Press

By Daniel Livesay

Sign up to save your library

With an OverDrive account, you can save your favorite libraries for at-a-glance information about availability. Find out more about OverDrive accounts.

Find this title in Libby, the library reading app by OverDrive.

Search for a digital library with this title

Title found at these libraries:

| Library Name | Distance |

|---|---|

| Loading... |

By tracing the largely forgotten eighteenth-century migration of elite mixed-race individuals from Jamaica to Great Britain, Children of Uncertain Fortune reinterprets the evolution of British racial ideologies as a matter of negotiating family membership. Using wills, legal petitions, family correspondences, and inheritance lawsuits, Daniel Livesay is the first scholar to follow the hundreds of children born to white planters and Caribbean women of color who crossed the ocean for educational opportunities, professional apprenticeships, marriage prospects, or refuge from colonial prejudices.

The presence of these elite children of color in Britain pushed popular opinion in the British Atlantic world toward narrower conceptions of race and kinship. Members of Parliament, colonial assemblymen, merchant kings, and cultural arbiters — the very people who decided Britain’s colonial policies, debated abolition, passed marital laws, and arbitrated inheritance disputes — rubbed shoulders with these mixed-race Caribbean migrants in parlors and sitting rooms. Upper-class Britons also resented colonial transplants and coveted their inheritances; family intimacy gave way to racial exclusion. By the early nineteenth century, relatives had become strangers.

The presence of these elite children of color in Britain pushed popular opinion in the British Atlantic world toward narrower conceptions of race and kinship. Members of Parliament, colonial assemblymen, merchant kings, and cultural arbiters — the very people who decided Britain’s colonial policies, debated abolition, passed marital laws, and arbitrated inheritance disputes — rubbed shoulders with these mixed-race Caribbean migrants in parlors and sitting rooms. Upper-class Britons also resented colonial transplants and coveted their inheritances; family intimacy gave way to racial exclusion. By the early nineteenth century, relatives had become strangers.