Sign up to save your library

With an OverDrive account, you can save your favorite libraries for at-a-glance information about availability. Find out more about OverDrive accounts.

Find this title in Libby, the library reading app by OverDrive.

Search for a digital library with this title

Title found at these libraries:

| Library Name | Distance |

|---|---|

| Loading... |

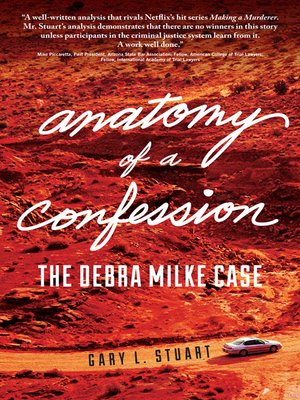

"A well-written analysis that rivals Netflix's hit series Making a Murderer. Mr. Stuart's analysis demonstrates that there are no winners in this story unless participants in the criminal justice system learn from it. A work well done." -Mike Piccaretta, Past President, Arizona State Bar Association; Fellow, American College of Trial Lawyers; Fellow, International Academy of Trial Lawyers

Anatomy of a Confession is the story of a 1990 murder trial. Two men murdered a four year-old boy. One of them casually implicated the boy's mother. Even before she was questioned, the police hung a guilty tag on her. The prosecutor believed it because the police did. The judge let the jury hear her confession, but not vital exculpatory evidence. The jury believed she did it because the cop was so convincing and the mother so unmotherly. That label came from her own family. No one in her courtroom presumed her innocence – not the cops, prosecutors, jurors, judge, or her own lawyer. America's most vaunted legal principle – the presumption of innocence – was nowhere to be found.

Debra Milke spent twenty-three years on death row for murdering her four year-old son based solely on a confession she never gave. The two men who killed Christopher Milke are still on death row. Neither testified against her, nor would they implicate her. Armando Saldate, the cop who took a true confession from one killer, could not break the other one. So, he made up a confession by the boy's mother. The trial judge hid damning impeachment evidence about Saldate. The jury believed the cop over the mother. They all believed her guilty. No one presumed her innocent.

It is also the story of the 2013 appellate decision by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. A three-judge panel reversed Milke's conviction because it was based entirely on a confession that may never have occurred. It said the State of Arizona remained "unconstitutionally silent" instead of disclosing information about Saldate's history of misconduct involving confessions. The court found that the evidence in Saldate's personnel file documented his "lack of compunction about lying during the course of his official activities." That evidence, the court said, would have been favorable to Milke's defense and likely would have affected her sentence. Because the state knew of the evidence in the personnel file, it had an obligation to produce the documents to the defense. In its most critical finding, the appellate court established the "law of the case." There was "a reasonable probability that disclosure of the evidence would have led to a different result."

Anatomy of a Confession also examines the Phoenix Police Department's role in the cover-up and a compliant prosecutor's misconduct in basing the entire case on a dubious confession. It tracks Armando Saldate's history and his methodical march to extract a confession without a witness, a recording, or any contemporaneous notes of what Debra Milke said, all of which violated written police procedures and the direct order of his supervisor. Twenty-five years have passed since Armando Saldate left the police department. The Milke case was his last. It has still not been resolved.

Anatomy of a Confession is a vivid reminder of what America's vaunted presumption of innocence is supposed to be all about, and what can happen when the criminal justice system fails and presumption of innocence becomes just the opposite, a presumption of guilt.

Author Gary L. Stuart teaches law and writing at Arizona State University. Prior to teaching, he practiced law for thirty-two years with one of Arizona's largest law firms. He has published dozens of law review articles,...