The European Byron

ebook ∣ Mobility, Cosmopolitanism, and Chameleon Poetry · Anthem Studies in Global English Literatures

By Jonathan Gross

Sign up to save your library

With an OverDrive account, you can save your favorite libraries for at-a-glance information about availability. Find out more about OverDrive accounts.

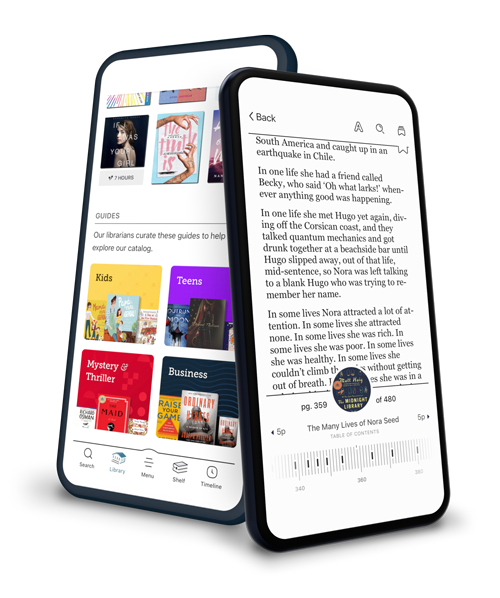

Find this title in Libby, the library reading app by OverDrive.

Search for a digital library with this title

Title found at these libraries:

| Library Name | Distance |

|---|---|

| Loading... |

Byron concealed himself in various literary disguises, a process he called "mobility." In this study of influences on Byron's verse and Byron's European impact, I explore these borrowings and transformations as they manifested themselves in his reading. At issue is the very concept of romantic poetic voice. Framing himself in the tradition of the Irish yet cosmopolitan Thomas Moore, Byron adopted continental guises, imitating both Italian writers and political heroes, such as Dante, Machiavelli, and Tasso. In establishing an Italian identity, Byron relied upon the Italian writers he translated (Pulci, Dante), Thomas Moore's "Fudge Family in Paris," and Shelley's "Julian and Maddalo," as well as Goethe's Faust. This Europeanization of Byron should not conceal the fact that Byron adopted poses from his predecessors, such as Walter Scott, in order to fashion himself as a Scottish poet who also happened to be English. Byron became the writers he read: Moore, Shelley, Wordsworth, Scott, Foscolo, Lady Morgan, and Madame de Staël. Those who imitated Byron, particularly Alexander Pushkin and Adam Mickiewicz, became the best interpreters of his literary example while transforming it, and explained what it meant to be a Harold in Muscovite Cloak, or a Polish Byron, to be both delimited and emancipated by Byron's example.